By Sabina Knight

Literature Professor & Author

Preventable blindness affects millions of people globally, and it costs only $25 to save a person from that fate. Imagine having had to adjust to the world with a serious visual impairment, having your sight restored, and then discovering that you could afford to fund 800 surgeries to restore sight to 800 blind individuals.

I never imagined it, but on December 9th I filled out a form to do just that. I hope you’ll read why and consider spending $25 to grant a person sight.

On September 30th and October 7th, a surgeon performed clear lens extraction (CLE) to correct my vision. (CLE is cataract surgery for patients who do not yet have cataracts but who suffer from other conditions that seriously impair their sight.) By this time, my vision had declined so seriously that, if I were not wearing glasses, I would often walk into doorframes. Without glasses, I was utterly unable to decipher a printed document in my hands. Not at all. I could not identify a person on the street until we were close. On my phone I could see only the time. Even with my glasses, texting felt like advanced acrobatics. My fingers felt impossibly clumsy. How did people tap the correct keys? I could barely see them.

Through observing a friend’s blind husband, I had learned techniques to avoid further accidents. I would trace the wall with my fingers when I went to the bathroom at night or if I couldn’t find my glasses. (I learned to remove my glasses only to sleep, wash my face or perform a few similar tasks.) Even with such newfound techniques, I had stopped riding my bike.

CLE changed my life. I can see the clock across the room. I can see the hands on my watch without squinting. I no longer panic if I can’t find my glasses in under a minute. I can see the settings and icons on my iPhone well enough to learn to use it. I can ride my bike. When dancing I can spot again. I no longer feel terror about my complete dependency on others if anything were to happen to my glasses during a time of crisis (such as a car accident or severe storm). I can again read for long periods. (I’m a literature professor and author, so reading is pretty important.)

What’s more, the world is awash in color. When I left the clinic and saw the blue sky, the world looked the way people who take psychedelics describe. My first thought was that, if the small dose of Fentanyl used for the surgery had such effects, I could see why people become addicted. My friend Macci, who had brought me, said that colors had been brighter after her first cataract surgery. Sure enough, the colors did not fade. Before the surgery I had not been color blind. I could identify colors, but I had been seeing the world through a very brown lens. Colors no longer strike me as psychedelic, but the vivid tones, especially blues, still amaze me every day. It is like a piece of childhood restored.

“The two photos from October were taken one week after my second CLE surgery. It was such a joy not to wear glasses!”

It’s funny. Before the surgery I had told many friends that the fall foliage in Western Massachusetts was no longer nearly as stunning as it had been when I first moved here 21 years ago. The experience reminds me not to presume that my beliefs or interpretations are true, nor even that my perceptions are true.

When I heard about CLE, it seemed too good to be true. (I was not a candidate for Lasik.) And when I learned that the best surgeon in our area was willing to do the surgery in my case, I felt as if I had been offered a lifeboat when I was drowning. Recovering my sight also renewed a sense of hope after a series of painful personal losses that had left me feeling even more vulnerable.

Regaining my sight helped me regain a sense of agency. During my appointment the day following the first surgery, my surgeon told me about his pro-bono work curing blindness in India. He sent me a link to a 28-minute film, Second Sight. (There’s also a one-minute Second Sight intro and trailer.) This documentary gave me a glimpse of how curing blindness affects individuals and their families. Toward the end I broke into tears. I wept and wept and wept. I watched it again. Knowing the end, I wept from start to finish.

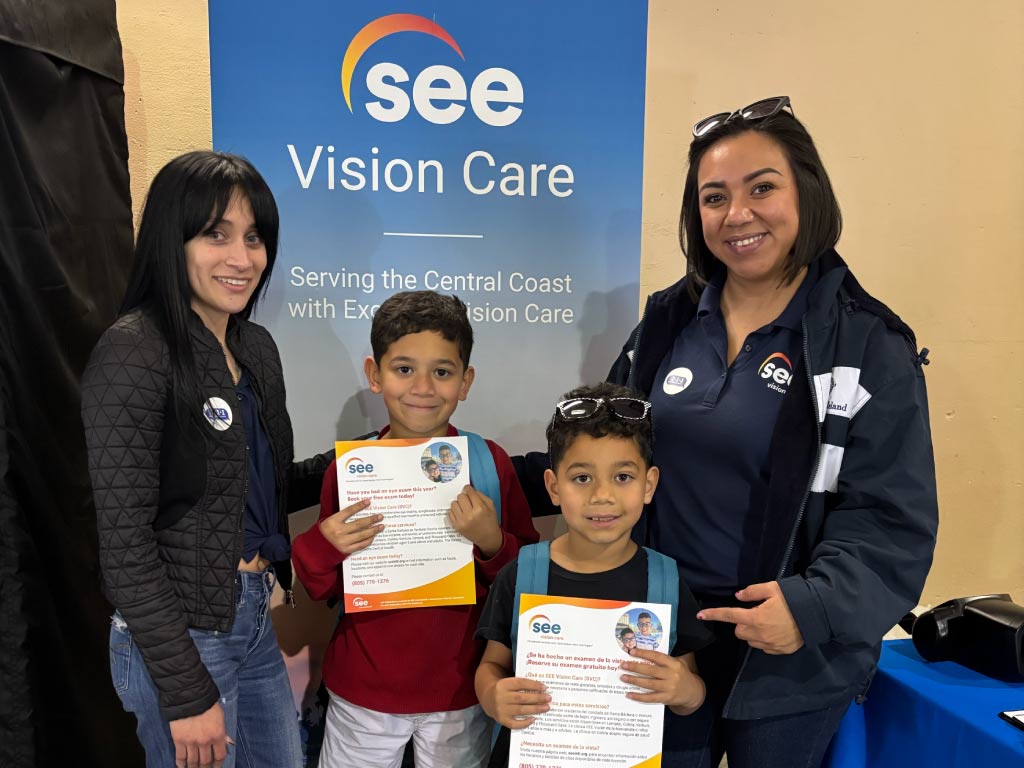

I later asked how much it costs to cure a person’s blindness. “At most $50 and probably less,” my surgeon answered. “What high impact!” I marveled. He agreed. He also pointed out that even better would be to develop infrastructure on the ground so that local surgeons could perform the surgeries. SEE International and similar organizations are doing that work too. He had researched several organizations before choosing to work with SEE (Surgical Eye Expeditions). And, knowing that organizations change, he monitors SEE’s use of funding. SEE has only become more efficient over time.

I am now giving the lion’s share of my tithe to SEE International. I sleep better at night knowing that I can steward and perhaps even help to raise funds to cure blindness. Easily treatable cataracts account for over a third of the world’s estimated 36 million blind people – a number expected to triple by 2050.

I was happy when I woke up the day after having mailed my letter for the donation. Would you want to feel the satisfaction of changing another person’s life and that of his or her whole family?

It costs only $25 for SEE and one of its volunteer surgeons (who pay their own airfare) to perform cataract surgery to restore a person’s sight.

Do you have your own visual impairment story you would like to share? Let us know!